Bread and Circus

The 2024 US Election and Politics as Entertainment

It is perhaps an encapsulation of wider American culture that our elections are so big, so boisterous, and so engaging. Take, for example, the ceremonial roll call at this year’s Democratic Convention, which had all the energy of a Eurovision broadcast—stirring music, giant cutouts of Harris and Walz’ faces, aisle dancing, and, in the case of Georgia, a Lil Jon performance (“DNC,” he said to cheers, “turn out for what?”).1

US elections have historically ranged from provocative to bizarre to hotly contentious. But it wasn’t until the mid-20th century that our national political landscape became so deeply enmeshed with our entertainment industry. Yes, candidates have always used political cartoons2, buttons3, rallies, and songs4 to drum up interest in their campaigns, and the invention of new technologies like the telephone and radio later extended that campaign reach. But it was the rise of the television that fundamentally altered how politicians connected with and catered to American citizens. If radio had allowed politicians to enter the American home for the first time, the television made it possible for politicians to become an inextricable part of the American family life, as unavoidable as Coca-Cola ads and the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

The 1952 Presidential election between Eisenhower (R) and Stevenson II (D) saw both candidates utilize televisual advertising as a key component of their campaign strategy. Eisenhower, who would go on to win the election, released a popular TV ad called ‘I like Ike’5; notably, the ad does not feature any mention of Eisenhower’s political stances or military career, or even footage of the candidate, and instead consists entirely of a bouncing cartoon parade with I LIKE IKE signs, singing a catchy jingle: ‘you like Ike, I like Ike, everybody likes Ike for President’.

The new focus on televisual campaigns was in part due to the rise of political consultants. Though political consultancy had existed in American politics in an informal capacity since the country’s inception, the technological transformations of the 20th century gave rise to political consultants as a fixed (and powerful) role within election campaigns. As early as 1956, political scientist Stanley Kelley Jr. spoke of the shift of the campaign manager from focusing on the internal workings of the political operation to the public perception of the candidate’s campaign, saying the ‘adman’ had replaced the party boss. Kelley notes that “[Eisenhower’s popularity] emphasized…the political advantages that accrue to anyone who holds what might be called a ‘position in the spotlight’—a position which attracts great amounts of free publicity in the normal course of news dissemination”.6 Start the conversation, it seems, and the media will do rest, granting you (and your talking points) a national prominence and publicity that regional organisation and word-of-mouth cannot.

The role of TV in presidential elections shifted again just a few years later. In 1960, John F. Kennedy (D) and Richard Nixon (R) went head to head in the first televised Presidential debate in US history. During the debate, Nixon, who had refused stage makeup7 before going on camera, began sweating under the studio lights. Producer Don Hewitt recalled Nixon looking like “death warmed over”8 and then-Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley afterwards quipped: “My God, they’ve embalmed him before he even died”.9 Suffice to say, Nixon’s wan appearance had an effect on the public consciousness, and despite his strong political performance in subsequent debates, Nixon lost the election to the more charismatic, TV-friendly Kennedy. Many historians believe his conduct in the first debate lost him the presidency, because his poor TV performance elevated Kennedy’s by comparison; in essence, it didn’t matter whether Nixon was actually weak, surly, or nervous, only that he appeared so when side-by-side with the young, confident Kennedy.

Compare the 1960 debate to the first 2024 Presidential debate between Donald Trump and Joe Biden—similarly to Nixon, Biden’s lacklustre performance worried the nation, amplifying reports of cognitive decline and unfitness for office. Despite forming an initial ring of support around Biden, the president’s allies eventually ceded to the public uproar, with Nancy Pelosi persuading Biden to bow out of the race and endorse VP Kamala Harris as the party’s nominee. The public opinion of Biden’s ineptitude reinforced the notion that public perception has an indelible impact on politics, and that candidates must focus on optics with the same fervor as they do policy.

As politicians have become entertainers, so have entertainers become politicians. Before Trump, there was Ronald Reagan, whose career as actor and host of ‘50s TV series General Electic Theatre paved his path to the White House. Movie star Arnold Schwartzenegger became the Governator only a few years after actor Jesse Ventura was elected Governor of Minnesota. These candidates were able to draw on their life as public figures to gain support in the political arena. Whereas career politicians had to work to gain the trust of American voters, Hollywood stars had to merely build upon parasocial bonds that already existed, accrued through years of visibility in the media and cashable now as political capital.

With Trump’s The Apprentice, like Reagan’s General Electric Theatre before him, Americans had welcomed him into their everyday routines, their homes, and their cultural lives, laying the groundwork to welcome him into their government.

Trump’s years in reality TV also served to establish him in the American mind as a strong businessman and smart entrepreneur, and his stint on The Apprentice presented him in an immensely favourable light not afforded most career politicians. As Eunji Kim and Shawn Patterson posit in their evaluation of the electoral consequences of The Apprentice: “in comparison to the traditional news media environment where political candidates actively counter their opponents’ messages, entertainment media usually provides a one-sided information flow”.10 In other words, Trump spent the vast majority of his early career not only unscrutinised by critics, but actually lionised by reality TV and one-sided information flow, at least as far as the average American was concerned. The television—and now, by extension, social media—has allowed for Trump and his viewers-cum-supporters to forge a political environment impervious to (or at the very least, ignoring of) oppositional criticism.

The 2010’s brought a further shift—from TV to social media. A 2017 PEW Research survey found that local television newscast audiences have dropped by a whopping 31% over the past decade.11 Americans are no longer getting their news from local sources, but from a hodgepodge of social media profiles and pundits.

These new platforms have created echo-chambers of misinformation that make it difficult to find out the truth. This vacuum has been used by Trump to further his agenda, forcing the Harris campaign to go after viral moments in an attempt to break through the noise. In the sunset days of the Biden campaign, memes began circulating of VP Harris’ coconut tree quote12 and edits of the VP to Charli XCX’s Brat, with posters declaring themselves—ironically and un-ironically— to be ‘coconut-pilled’ members of the ‘K-hive’. When Biden dropped out and Harris stepped up, Charli XCX declared on Twitter ‘kamala IS brat’13, breathing further meme shelf-life into the nascent campaign. Gone are the old guard, Harris’ campaign promised, here comes the cool zeitgeist-y stepmom to the young people. This would be all well and good if her policies reflected more progressive views as favoured by young voters—in particular, a new policy approach to the Gaza genocide and the Middle East—but they do not.14 Perhaps not a deposing of the old guard, then, but an expensive facelift.

Trump, meanwhile, has courted the manosphere, eschewing traditional media interviews with trained journalists who would fact-check him15 for a series of off-the-cuff interviews on bro podcasts. Kamala responded by appearing on Call Her Daddy and SNL. Trump replied to a recent Biden flub comparing Trump’s base to ‘garbage’ by posing with a garbage truck.16 Recent TikToks by Harris’ campaign channel, KamalaHQ, include captions like: ‘ya’ll want this??? for president??’ beside a photo of Trump, ‘halloween might be over but i know she scares tf outta trump’ across a picture of Harris on the campaign trail, as well as one simply saying: ‘lmao joe rogan clocked trump’. Aren’t we entertained? Sure. But among all the memes and viral moments, it feels like we’re in danger of losing sight of the actual politics of it all.

Competition for attention, engagement, and votes has made political life into campaign, and policy into product. There are many pressing issues facing Americans right now. The US education system is facing slashed funds and suppressed academic freedom17. Climate disasters are wiping out entire communities18, reproductive healthcare rights are disappearing19, racist rhetoric is being given a national stage20, food is being recalled from grocery stores at record rates21, and the threat of post-election political violence looms22.

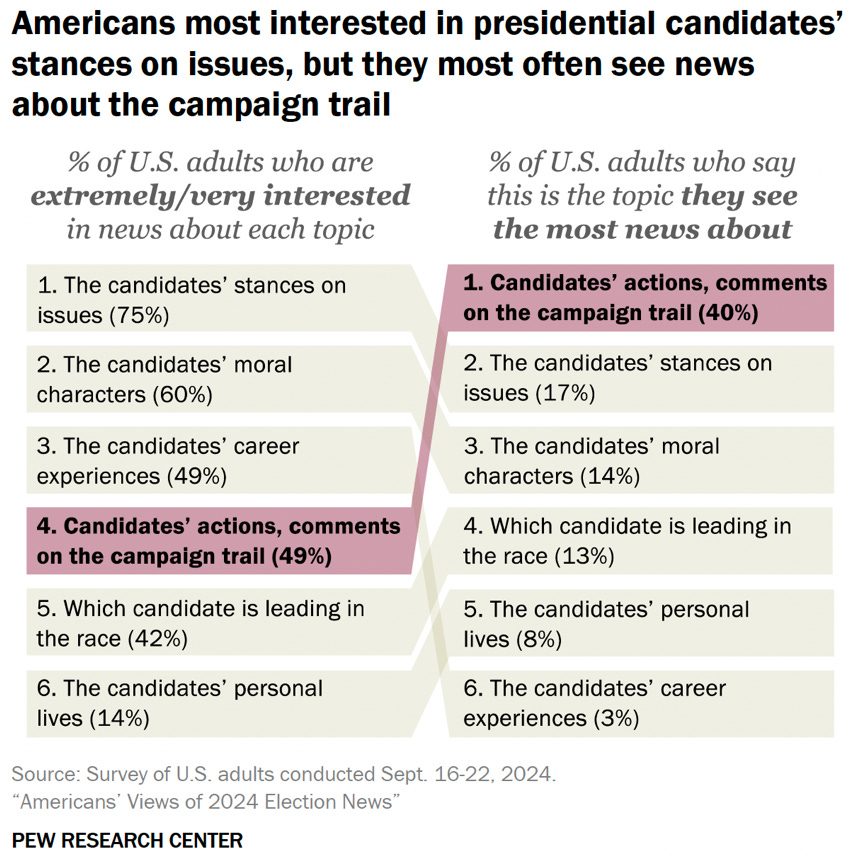

In an October research report by PEW, “American’s Views on 2024 Election News”, a survey found that they when it comes to Presidential race news, Americans are most interested in candidates’ stances on issues, moral character, and career experience. But that’s not the coverage they’re seeing in the media. 40% of those surveyed say they see the most news not about the candidates qualifications, but about their actions on the campaign trail. People know broadly that Harris has replaced Biden and that Trump faced an assassination attempt at a rally in July, but hear less about other topics they want to know about: specific policy proposals, moral character, and candidates’ political experience. The results, depicted in the PEW figure below, show a clear misalignment between what Americans want to know about presidential candidates and their campaigns and the information the campaigns and media deem important.

This election has become a theatrical arms-race, where our allegiance to a certain candidate is based not merely on our alignment with their values, but on vibes—who had the most titillating comment, who had the snappiest response to that comment? In a media landscape with an endless scroll, do we no longer have the attention span23—or the stomach—for engaging with questions of political values, experience, or aptitude? I see the value in using social media as a campaign tool, I really do. It’s a smart way to mobilise previously apathetic demographics to engage with politics and hopefully drive them to the polls on Tuesday, and it makes political language accessible beyond a civics class, and that accessibility can translate to direct action. But too much of this also feels, to me, profoundly worrying. What does it do to us to collapse the policies that affect our lives into flat, market-tested content, to meme-ify our moral values beyond recognition, and to erode the boundary of political election into something more closely resembling fandom?

The phrase ‘bread and circuses’ comes from a poem attributed to satirical 1st c. Roman poet Juvenal (but which I, full disclosure, first encountered in Suzanne Collins’ equally seminal Hunger Games novel Mockingjay) and means to offer us entertainment as appeasement, a substitution for transformative public policy and services that would improve citizens’ lives.

[The Roman mob] That used to grant power, high office, the legions, everything,

Curtails its desires, and reveals its anxiety for two things only,

Bread and circuses.24

Though often interpreted as a criticism of the short-sightedness of the general populace, I would argue that ‘bread and circuses’ more accurately describes a tactic of those in power to pacify their subjects with short-term amusement to avoid drawing attention to the deep-rooted problems created by selfish political action. America has a long history of using politics as entertainment, but at what point does the latter outpace the former? And can we, in a (finger’s crossed, breath held) post-Trump America, put that genie back into the bottle? The American people deserve more than just bread and circus distractions, we deserve meaningful legislation, and I hope tomorrow we will move towards that future.

Further reading:

Archer, Alfred, et al. "Celebrity, democracy, and epistemic power." Perspectives on Politics 18.1 (2020): 27-42.

A. Freya Thimsen. “Populist Celebrity in the Election Campaigns of Jesse Ventura and Arnold Schwarzenegger.” The Velvet Light Trap 65 (2010): 44 - 57.

Lawrence, Regina & Boydstun, Amber. (2017). Celebrities as Political Actors and Entertainment as Political Media. 10.1007/978-3-319-60249-3_3.

MOSKOWITZ, DANIEL J. “Local News, Information, and the Nationalization of U.S. Elections.” American Political Science Review 115.1 (2021): 114–129.

Nussbaum, Emily. "The TV That Created Donald Trump." The New Yorker 31 (2017).

C-SPAN. “Lil Jon at the Democratic National Convention.” YouTube, 20 Aug. 2024, www.youtube.com/watch?v=YzyTA-XfmY4.

“Search Results from Cartoon Prints, American, Available Online.” The Library of Congress, 2015, www.loc.gov/collections/american-cartoon-prints/.

“Campaign Buttons from Past Elections.” CNN, 3 Nov. 2016, edition.cnn.com/2016/11/02/politics/gallery/tbt-campaign-buttons/index.html. Accessed 3 Nov. 2024.

NPR. “The History of Presidential Campaign Songs Goes back to George Washington.” NPR, 21 Aug. 2024, www.npr.org/2024/08/21/nx-s1-5049733/the-history-of-presidential-campaign-songs-goes-back-to-george-washington.

New York Historical Society. “Presidential Ad: “I like Ike” from Dwight D. Eisenhower (R) vs. Adlai Stevenson II (D) [1952—HOPE] - YouTube.” Www.youtube.com, www.youtube.com/watch?v=YP7WaUPACuY.

Stanley Kelley Jr. Professional Public Relations and Political Power, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1956), 199–200.

“Nixon Calls Makeup on TV a Big Factor in His 1960 Defeat.” The New York Times, 23 Nov. 1967, www.nytimes.com/1967/11/23/archives/nixon-calls-makeup-on-tv-a-big-factor-in-his-1960-defeat.html.

60 Minutes Staff. “1960: First Televised Presidential Debate.” Cbsnews.com, 4 Oct. 2012, www.cbsnews.com/news/1960-first-televised-presidential-debate/ .

Donaldson, Gary (2007). The First Modern Campaign – Kennedy, Nixon, and the Election of 1960. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742547995. p.128.

KIM, EUNJI & PATTERSON, SHAWN. (2024). The American Viewer: Political Consequences of Entertainment Media. American Political Science Review. 1-15. 10.1017/S0003055424000728.

NW, 1615 L. St, et al. “Trends and Facts on Local News | State of the News Media.” Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project, 13 July 2021, www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/local-tv-news/.

CBS News. “Watch Kamala Harris’ Viral “Coconut Tree” Remarks.” YouTube, 23 July 2024, www.youtube.com/watch?v=0bSTqokjNEE.

“kamala IS brat” X (Formerly Twitter), 2024, x.com/charli_xcx/status/1815182384066707861?lang=en.

Adel Abdel Ghafar, and Aylin Salahifar. “Biden vs Harris on the Middle East: Same Dance, Different Steps.” Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 8 Aug. 2024, www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2024/8/8/biden-vs-harris-on-the-middle-east-same-dance-different-steps.

“A Statement from 60 Minutes.” CBSnews.com, CBS News, 20 Oct. 2024, www.cbsnews.com/news/60-minutes-statement/.

“Donald Trump Garbage Truck Video Shows Stunt to Trash Joe Biden.” BBC News, www.bbc.co.uk/news/videos/c5yr73430lxo.

Bonitatibus, Steve. “Project 2025’S Elimination of Title I Funding Would Hurt Students and Decimate Teaching Positions in Local Schools.” Center for American Progress, 25 July 2024, www.americanprogress.org/article/project-2025s-elimination-of-title-i-funding-would-hurt-students-and-decimate-teaching-positions-in-local-schools/.

Ducroquet, Simon. “See How Hurricane Helene Became One of the Century’s Worst Disasters.” Washington Post, The Washington Post, 5 Oct. 2024, www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/interactive/2024/helene-flooding-damage-north-carolina-chimney-rock/.

Kelner, Martha. ““Women Are Losing Their Lives”: The US State Where Abortion Rights Could Sway the Vote.” Sky News, Sky, 13 Oct. 2024, news.sky.com/story/women-are-losing-their-lives-the-us-state-where-abortion-rights-could-sway-the-vote-13233177.

Gabbatt, Adam, and Ed Pilkington. “Trump Fills Madison Square Garden with Anger, Vitriol and Racist Threats.” The Guardian, The Guardian, 28 Oct. 2024, www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/oct/27/trump-madison-square-garden-rally.

Ries, Julia. “What’s the Deal with All the Food Recalls and Outbreaks Lately?” HuffPost UK, 28 Oct. 2024, www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/food-recall-listeria-ecoi-outbreak_l_671c09c9e4b0fdf4fef464ca.

“1 in 5 Americans Think Violence May Solve U.S. Divisions, Poll Finds.” PBS NewsHour, 3 Apr. 2024, www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/1-in-5-americans-think-violence-may-solve-u-s-divisions-poll-finds.

Mills, Kim. “Speaking of Psychology: Why Our Attention Spans Are Shrinking, with Gloria Mark, PhD.” Apa.org, American Psychological Association, Feb. 2023, www.apa.org/news/podcasts/speaking-of-psychology/attention-spans.

Kline, A. S. “Juvenal (55–140) - the Satires: Satire X.” Www.poetryintranslation.com, 2001, www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Latin/JuvenalSatires10.php. SatX:56-113 The Emptiness Of Power

Really well-researched and thought-provoking commentary - this gives in-depth background I wasn't aware of and crstallises the unease I've felt watching the presidential election from here in the UK. We'll see what unfolds...